The John Ireland Bridge over I-94 is closed for several months due to construction. Please visit the MNDot website for more information.

John Olaf Todahl and The Petrified Man

By: Amy Padden

Place: Finalist

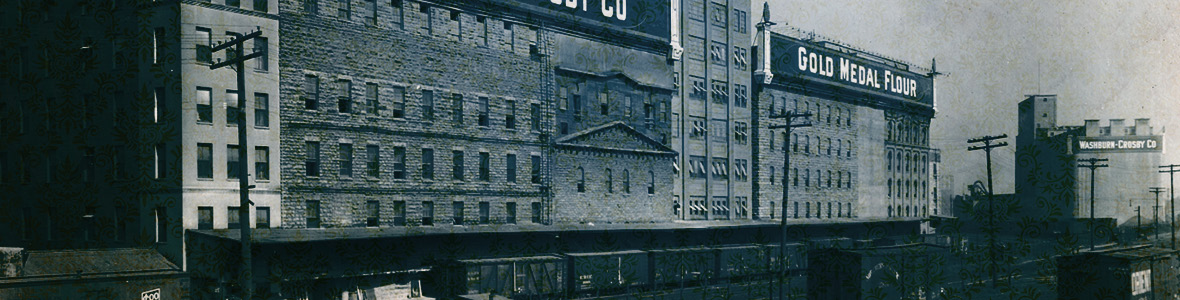

1915: Minneapolis

“…it’s murder,” a voice hissed.

Wanda leaned in to listen.

“Come and join us, Miss Gág,” a deeper voice called out. “No need to hover at the door.”

Wanda Gág, a student at the Minneapolis School of Art, absently patted her dark curls and walked into the office, feeling like a caught child. The building was hot and stuffy, the July air heavy, and she was glad she’d worn her green linen dress.

Herschel V. Jones of the Minneapolis Journal sat there, chest puffed out, clearly pleased he’d caught her peeking in. Besides paying for her schooling and supplies, Jones would often recommend her to anyone wanting a portrait done.

She didn’t recognize the other two men but they seemed like they would be more at ease in a mill than in her studio, their shoes covered in a faint dusting of flour. And she hardly felt her rates could be called murder. Maybe she’d bring Inky, her calico cat, to the two men’s portrait sittings. Inky was good at making people smile and the three men were being very serious.

“Thank you for coming today, Miss Gág. This is Mr. Bauer,” Jones said, pointing to a young man with shaggy brown hair who couldn’t be much older than she was, “and Mr. Maes,” he added, gesturing to a pale man with glasses and fluffy, blond hair. “They are from the Mill City Mill and need help.”

Mr. Maes pushed back his chair. He moved too quickly though and knocked it against the wall.

“You are wasting your time, Mr. Jones,” Maes said. “We do not need her help.”

Bauer watched him go; his face pinched as if he’d eaten something sour. Nodding to Jones, Bauer said, “Sir,” and, with barely a glance at Wanda, left too.

Jones watched them leave and then took off his glasses and rubbed his eyes. “They’re under a lot of pressure. How much do you know about the mills?”

She shrugged and sat down. “Just what the Minneapolis Journal tells me...”

Jones gave her a wan smile.

“…that Minneapolis is the Flour-Milling Capital of the World.”

“Well,” Jones said. “One of the Mill City Mill’s foremen hasn’t shown up to work in the past fortnight and even before that, their production was down. I need you to figure out why.”

“I’m an artist, not a detective.” She spent her days in the classroom or studio. The school had moved into the newly constructed Minneapolis Institute of Art and she was hoping to help with the water color exhibit that was opening in the fall. Not solve a mystery.

“You can do both. You have an exceptional eye for detail; there could be something that you’ll see that everyone else overlooked. We have to get that flour, all of it, to those that are hungry.” Jones hit the desk.

At twenty-two, she’d been following the plight of those affected by the war like many others in America. She shook her head. “I’m not sure…”

“The war has disrupted everything in Europe. People will starve.”

Ah, she thought. It was not her rates that were murder but that people might really die. And they were asking her to help. How could she say no.

“Alright, when do Inky and I start?”

The next day Inky burrowed into Wanda’s arms—she’d told the mill the cat was an excellent mouser.

“Ah, Miss Gág. This way.” It was Mr. Maes, his earlier dislike of her having been replaced with a forced smile.

“We told everyone that you were here to show the good work Mill City Mill is doing.” Mr. Bauer said, coming up right behind Maes with a slightly more genuine smile. “So, you’ll have access to all the war records and can poke about wherever you need to. And since it’s temporary work, you’ll be on your own.”

Good thing she had Inky, she thought, frowning, or this was going to get lonely fast.

“In January,” Maes said, not seeming to notice her reaction, “we were working at capacity—producing enough flour to make seven million loaves a day for that first delivery to Europe. Now we produce enough to make just under six.”

“And there are many, many in need,” Bauer said.

Inky shifted in her arms and Wanda sighed. “Where do we start?”

The two men lead her to a windowless room with a weak lightbulb and a single desk and chair. Pulling out a ledger to prove their numbers were correct and there was indeed a lot of flour missing, Bauer and Maes handed her a big stack of files and excused themselves.

Setting Inky down, Wanda shooed her off. “Go on, Inky. Make yourself useful and catch a mouse. Or, better yet, find out who’s sabotaging the mill so we can go back to school.”

Inky slinked off and Wanda sat at the desk, waving away the cloud of dust that poofed out from the chair. The room’s walls were lined with metal file cabinets and the floor hummed from the mill’s machines and activity, making it hard to think straight.

The top file was the missing foreman. Interestingly, his name was Maes too. She wondered if it was a common surname or if he was related to the surly Mr. Maes she’d already made acquaintance with. Flipping through the other files, she saw her Mr. Maes was also a foreman. That must have gotten very confusing down on the floor.

Mr. Bauer was in the second file and seemed to be in charge of shipping. She wondered if his department was the one getting blamed for the missing flour.

Unsure who any of the other employees were in the stack of files, she decided to go down to the factory. Maybe there was a problem with one of the machines? It seemed unlikely that no one would have noticed a giant pile of flour on the floor...

Inky jumped up into her lap.

“Alright, you can come with,” Wanda said to her.

Together they followed their ears down to the factory floor. Staying along the wall, she tried to figure out the ebb and flow of the mill, wandering around the offices and machines, watching and listening. She wasn’t sure for what. The input coming into the mill was steady; the grain got delivered, was ground up, packaged, and shipped. It was just the output that was going down.

But after three days, Wanda noticed what no one else had. Grabbing Inky, she went over to get a better look, gasped, and ran upstairs to the records room.

Finding what she needed, they slipped out of the mill. There was a factory they had to go visit.

Originally, flour had been packaged in barrels but now it went into cotton sacks. And it was one of those sacks that had caught Wanda’s attention.

Like the mill, the factory was loud but here most of the workers were women. After a few questions to a stern-faced, grey-haired woman in charge of the floor, and who clearly did not approve of a cat in her factory, Wanda left.

Hurrying over to Jones’ office, ignoring the sun beating down, she burst in and gasped, “It’s the bags. The missing flour is in the bags.”

Jones didn’t say anything, his face expectant, waiting for her to continue.

Wanda collapsed into a chair, fanning herself with her hand. “The bags are in German,” she said finally. “Not all of them, but I’d warrant the missing amount is.”

Jones stood up. “Show me.”

The mill floor was absent of any of the German bags by the time they got there. Watching Inky disappear under a tarp in the back of the shipping area, she led Jones past Bauer and pulled the cloth aside.

“Seems I’ve found the missing flour, Mr. Bauer,” Wanda said. “Or maybe you knew it was here all along?”

His shoulders sank.

“Is the Miss Bauer at the bag factory a relation of yours?” Wanda asked him. “The woman I spoke to had a lot to say about Miss Bauer’s love for her homeland.”

He nodded. “My sister.”

“And the flour?”

“People are so very anti-German after the Lusitania,” Bauer said. “And there are hungry children in Germany too. Blasted British blockade. We wanted to help everyone.”

“What about the foreman?” Jones asked.

“Maes shipped off wanting to help his country.”

“And you didn’t mention that?” Wanda asked.

“It kept people from asking me too many questions,” Bauer said hanging his head.

“But how did no one notice?” Jones was staring at the bag of flour. Its design was the same as the American bags but was written in German.

Wanda smiled. “I’m sure since the workers stare at the same thing day after day, they don’t they really see the bags. As you said, only an artist would.”

About the author

A.L.Padden loves history. She lives in the Twin Cities with her husband, boys, and rescue dog, Watson.

Her poem “BONNIE AND CLYDE” was displayed at the Hennepin History Museum and for the past three years she has taught at the SavvyAuthor WriterCon. She is a member of The Loft Literary Center, Sisters in Crime, and the Minneapolis Writers Workshop.

When she's not writing, she is reading with a cup of tea or paddle boarding and cross-country skiing.