Enslaved African Americans and the Fight for Freedom

Enslaved African Americans and the Fight for Freedom

By the time Fort Snelling was built in the 1820s, slavery was a reality in the Northwest Territory. Fur traders often utilized the labor of enslaved people and some officers at the post, including Colonel Josiah Snelling, owned enslaved people. Other officers rented the use of enslaved people from US Indian Agent Lawrence Taliaferro. It is estimated that throughout the 1820s and 1830s anywhere from 15 to more than 30 enslaved African Americans lived and worked at Fort Snelling at any one time. These people likely cooked, cleaned, and did laundry and other household chores for their enslavers.

The officers and civilians who enslaved African Americans at the confluence were in violation of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which stated that slavery was forbidden in the territory gained through the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36°30' latitude line (except within the boundaries of the state of Missouri). Slavery had existed in this region prior to the compromise, however, and it continued in spite of it.

US Army officers received extra pay to retain a servant, something that was expected in the rigid class structure of the military. Some officers utilized enslaved labor instead, adding the extra pay to their overall income. Officers submitted pay vouchers, often using the descriptor “slave,” to collect this extra pay, which was provided to no other government officials. The US Army thus incentivized slavery and essentially paid its officers for enslaving people.

When the First United States Infantry Regiment replaced the Fifth United States Infantry Regiment at Fort Snelling in 1828, slavery at the confluence entered its peak years. The commander of the unit was Lieutenant Colonel Zachary Taylor, future president of the United States. At least seven enslaved people had lived at the fort under the Fifth Infantry, but under the First Infantry, the number swelled to 30 or more. Indian Agent Taliaferro seized the opportunity and imported more enslaved people to the confluence, becoming the region’s largest slaveholder.

Slavery continued at Fort Snelling, ending just before Minnesota statehood in 1858. The practice of slavery spread to newly constructed Fort Ridgely in 1854. From 1855 to 1857, no fewer than nine people were enslaved at Fort Snelling, the highest number since the 1830s. Slavery at the fort did not end because of legal action. The Tenth United States Infantry Regiment, the last slave-holding unit to garrison the fort, was transferred to Utah in 1857.

Rachel and Courtney’s suits for freedom

The vast majority of enslaved people at Fort Snelling had no legal recourse to defend themselves. However, four enslaved people — two women named Rachel and Courtney, and the famous married couple, Harriet Robinson Scott and Dred Scott — are known to have challenged their illegal enslavement at Fort Snelling in the courts.

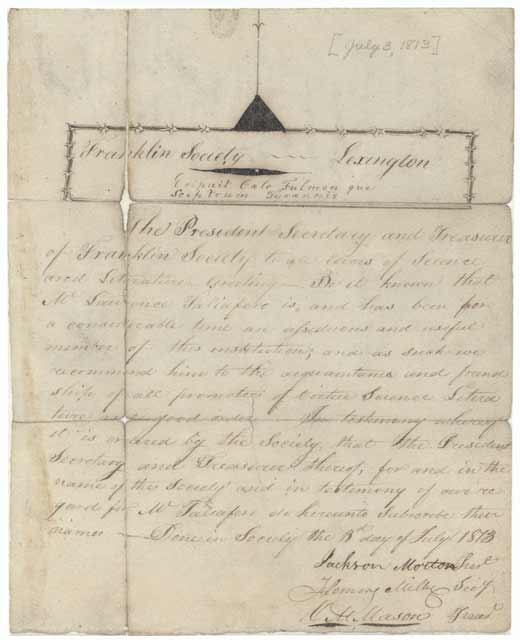

Elias T. Langham procured an African American woman named Rachel at St. Louis in 1830 for Lieutenant Thomas Stockton. Stockton enslaved Rachel at Fort Snelling for a year and then at Fort Crawford at Prairie du Chien until 1834. While at Fort Crawford, Rachel gave birth to a son, James Henry. Stockton took Rachel and her son to St. Louis and sold them to a slave dealer. Rachel sued for her freedom in Missouri court, arguing that she had been illegally enslaved in free territory at Fort Snelling and Prairie du Chien. In June 1836 the Missouri Supreme Court ruled in her favor, and Rachel and her son were set free.

Courtney’s case overlapped with Rachel’s. Fur trader Alexis Bailly sold Courtney and her son William to a prominent slaveholder in St. Louis in 1835. Courtney sued for her freedom and convinced a lawyer to take her case. With Rachel’s case ongoing, Courtney deemed it prudent to wait for a decision. When Rachel was declared free, Courtney became free as well.

Even though the freedom suits of Rachel and Courtney affirmed that enslavement was illegal at the confluence, the practice continued.

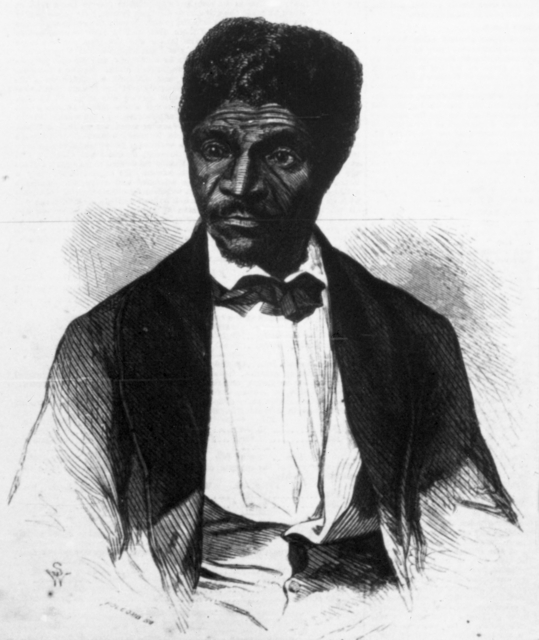

Dred and Harriet Scott

Dred and Harriet Scott were enslaved African Americans belonging to Dr. John Emerson, Fort Snelling’s surgeon from 1836–40. Both Dred and Harriet were likely born in Virginia, but their birth dates are unknown. Dred was purchased by Emerson, an army doctor stationed at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, from his original owner, Peter Blow. Travelling with Emerson, Dred spent time in Illinois and Iowa before Emerson was transferred to Fort Snelling in 1836. After arriving at the fort, Dred met Harriet Robinson, an enslaved woman owned by Indian Agent Lawrence Taliaferro. Dred and Harriet were soon married in a ceremony officiated by Taliaferro, who then either gave or sold Harriet to Emerson.

The Scotts remained at Fort Snelling until 1840, when Emerson was assigned as a medical officer in Florida during the Seminole War. Emerson's wife, Irene, moved to St. Louis with Dred, Harriet, and their daughter Eliza, and they remained there until Dr. Emerson was discharged from the Army in 1842. After Dr. Emerson's death in 1843, Irene Emerson became the owner of the Scott family. In 1846 the Scotts sued Irene Emerson in the St. Louis County Court for their freedom. Successful freedom suits, such as the one filed by Rachel in the 1830s, may have prompted the Scotts to seek out assistance from anti-slavery supporters in St. Louis. In addition, the Scotts had two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, who by the 1840s had reached the age where they could be sold away, which may also have spurred the Scotts into action.

The Scotts’ case was based on the fact that they lived as enslaved people in free territory at Fort Snelling and other places, and therefore should be granted their freedom. The Scotts lost their initial trial, but they appealed the decision and were granted their freedom in January 1850. Irene Emerson appealed the verdict, and the case was sent to the Missouri Supreme Court in 1852 where the Scotts lost. In the meantime, Irene Emerson transferred ownership of the Scotts to her brother, John Sanford, who lived in New York. Because the case then involved residents of two different states (Missouri and New York), there was precedent to have it tried in a federal court. The Scotts filed suit in the Missouri federal court in 1853, and after losing the following year appealed the decision to the US Supreme Court in February 1856.

In March 1857 the US Supreme Court decided, 7-2, that the Scotts would remain enslaved. The majority opinion stated that as enslaved people, the Scotts were considered property that could be taken anywhere by their owners, regardless of whether or not a particular place banned slavery. The court went even further, declaring that enslaved African Americans were not citizens and had no right to bring cases to court in the first place. According to Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, African Americans “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.” The court intended the decision to settle the issue of slavery, but it only inflamed the debate.

The Dred Scott decision was a landmark case in the national debate over slavery. The Supreme Court’s decision effectively declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, thereby opening the door for the spread of slavery throughout the US and its territories. Abolitionists and anti-slavery advocates were outraged, while southern slavers cheered the decision. In June 1857 the Scott family and their story were featured on the front page of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, one of the most widely-read periodicals in the US at the time. Tensions increased between the North and South, and the nation was pushed further toward civil war. The decision greatly influenced the nomination of Abraham Lincoln, who opposed the Dred Scott decision, by the Republican Party for the presidential election of 1860.

One month before the decision, it was reported that Irene Emerson had recently married Calvin Chaffee, an anti-slavery politician from Massachusetts. To avoid a scandal, Chaffee arranged to transfer ownership of the Scotts to Missouri resident Taylor Blow, who subsequently freed the Scotts on May 26, 1857. Both Dred and Harriet remained in St. Louis where they worked as free people. Dred died of tuberculosis on September 17, 1858, while Harriet lived in St. Louis until her death on June 17, 1876.

Resources

- Atkins, Annette. “Dred and Harriet Scott in Minnesota.” MNopedia, October 13, 2014.

- Bachman, Walt. Northern Slave, Black Dakota: The Life and Times of Joseph Godfrey. Bloomington, MN: Pond Dakota Press, 2013.

- Boorom, Jeffrey C. "Slavery at Fort Snelling in the 1820s." Historic Fort Snelling, 2007.

- Burnside, Tina. "African Americans in Minnesota." MNopedia, July 26, 2017.

- DeCarlo, Peter. Fort Snelling at Bdote: A Brief History. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2017.

- "Dred & Harriet Scott: Slaves in a Free Territory: Overview," Minnesota Historical Society, https://libguides.mnhs.org/dscott.

- Green, William D. A Peculiar Imbalance: The Rise and Fall of Racial Equality in Early Minnesota. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007.

- Grivno, Max L. "African-Americans at Fort Snelling, 1820-1840: An Interpretive Guide; Research Paper," Historic Fort Snelling, 1997.

- Hess, Jeffrey A. "Dred Scott: From Fort Snelling to Freedom." Fort Snelling Chronicles, no. 2. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 1975.

- Lehman, Christopher P. Slavery in the Upper Mississippi Valley, 1787–1865. Nefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2011.

- Maijala, Kevin. "Interpreting African-Americans and Slavery at Fort Snelling." Historic Fort Snelling, May 2007.

- Swain, Gwenyth. Dred and Harriet Scott: A Family's Struggle for Freedom. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2004.

- VanderVelde, Lea. Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery's Frontier. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.