The Fur Trade

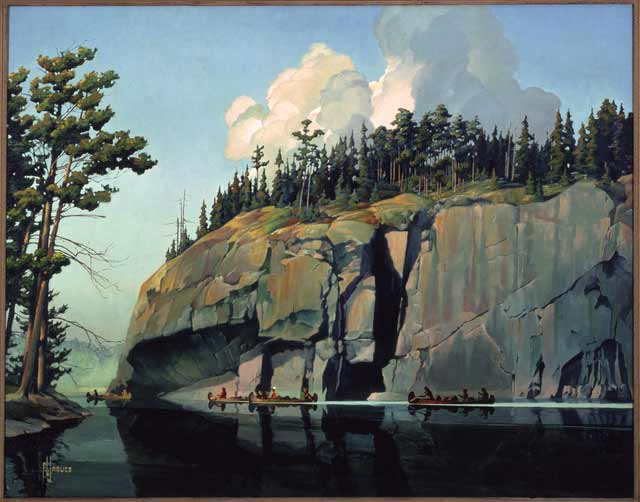

Native Americans traded along the waterways of present-day Minnesota and across the Great Lakes for centuries before the arrival of Europeans in the mid-1600s. For nearly 200 years afterward, European American traders exchanged manufactured goods with Native people for valuable furs.

The Ojibwe and Dakota held powerful positions, prompting both the French and British to actively court their military and trade allegiance. Trade with Native Americans was so critical to the French and British that many European Americans working in the fur trade adopted Native protocols. The Ojibwe were particularly influential, which led many French and British people to favor Ojibwe customs of bartering, cooperative diplomacy, meeting in councils, and the use of pipes.

Following the American Revolution, the US competed fiercely with Great Britain for control of the North American fur trade. After the War of 1812 there were three main parties involved in the Upper Mississippi fur trade: Native Americans (primarily the Dakota and Ojibwe), the fur trading companies, and the US government. These parties worked together and each had something to gain from a stable trading environment. Both Fort Snelling and the Indian Agency were established by the US government at the junction of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers to control and maintain the stability of the region's fur trade.

By 1823, the American Fur Company controlled the fur trade across much of present-day Minnesota. The company’s headquarters was at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers, at a post called New Hope, or more commonly called St. Peters. Today it is called Mendota, derived from the word Bdote. The post was managed by Alexis Bailly, who began running a series of trading posts that extended up the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers. Henry Hastings Sibley, who took Bailly’s place in 1834, ran the Western Outfit of the American Fur Company and was responsible for trade with the Dakota.

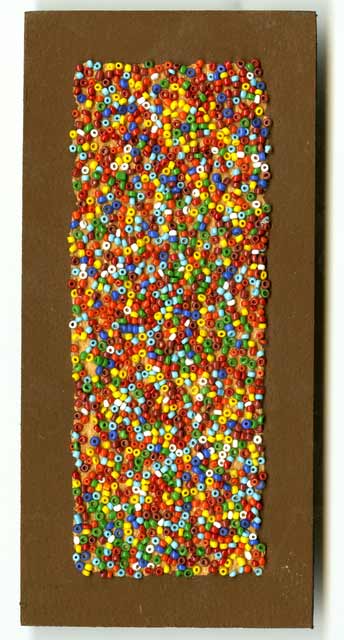

The Dakota and Ojibwe were the primary trappers of fur-bearing animals in the Northwest Territory. They harvested a wide variety of furs (beaver being the most valuable) in the region's woodlands and waterways. In exchange for these furs, French, British, and US traders provided goods such as blankets, firearms and ammunition, cloth, metal tools, and brass kettles. The Dakota and Ojibwe had existed for thousands of years using tools made from readily available materials, but by the 1800s trade goods had become a part of daily life for many Native communities. Some Dakota and Ojibwe communities became dependent on trade goods for a certain level of prosperity and efficiency in their everyday lives. The fur trade had a tremendous effect on Dakota and Ojibwe cultural practices and influenced US-Native economic and political relations in the 19th century, including treaty negotiations.

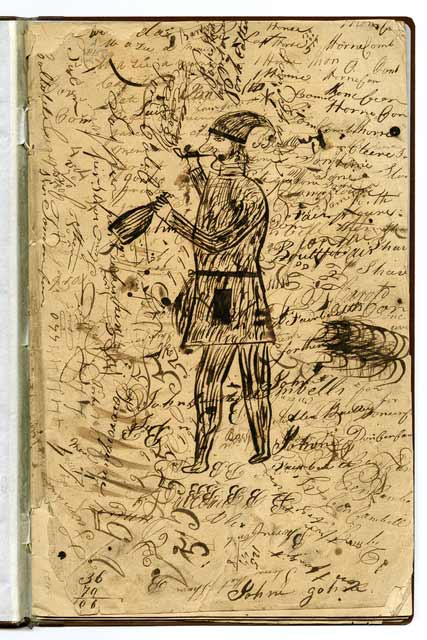

Voyageurs ("travelers" in French) were men hired to work for the fur trade companies to transport trade goods throughout the vast territory to rendezvous posts. At the rendezvous points, these goods were exchanged for furs, which were then sent to larger cities for shipment to the east coast. Many traders and voyageurs married Native American women and were integrated into their Native kinship networks, often trading exclusively within their particular community. As a result of generations of intermarriage, large communities of individuals of diverse heritage developed, often called "mixed-bloods" or “half-breeds” during the period, and many of these individuals maintained ties to both the fur trade and Native communities.

George Bonga, the son of a former slave and an Ojibwe woman, married an Ojibwe woman and was active in the fur trade during the first half of the 1800s. Bonga was educated in Montreal and was well-known for his physical stature and strength. Often sought out for his skills as an interpreter, Bonga could speak French, English, and Ojibwe. The Bonga family is just one example of the diversity and cultural exchange that resulted from the fur trade in the Northwest Territory.

Slavery also played a part in the fur trade, as some traders and fur company employees (including Jean Baptiste Faribault and Hypolite Dupuis) utilized the labor of enslaved people. There is speculation as to whether Henry Hastings Sibley enslaved someone at his trading post, because it is unclear as to whether or not Joe Robinson, his cook, was a free man. In some cases these enslaved people were freed by their masters, but often they remained part of the trade business.

By the 1840s the fur trade had declined dramatically in the Minnesota region, partially due to changes in fashion tastes, the availability of less-expensive materials for hat-making, and because the US government reduced Dakota and Ojibwe hunting grounds through treaties. For many Dakota and Ojibwe people, who had by this time become increasingly dependent on the trade, exchanging land in order to pay off debts claimed by traders became a matter of survival.

Resources

- Anderson, Gary Clayton. Kinsmen of Another Kind: Dakota-White Relations in the Upper Mississippi Valley, 1650–1862. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

- Brown, Jennifer S. H. Strangers in Blood: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1980.

- "Fur Trade in Minnesota: Overview," Minnesota Historical Society, https://libguides.mnhs.org/furtrade.

- Gilman, Carolyn. Where Two Worlds Meet: The Great Lakes Fur Trade. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1982.

- Gilman, Rhoda R. Henry Hastings Sibley: Divided Heart. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2004.

- Green, William D. A Peculiar Imbalance: The Rise and Fall of Racial Equality in Early Minnesota. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007.

- Lurie, Jon. "Fur Trade in Minnesota." MNopedia, January 26, 2021.

- Nelson, George. My First Years in the Fur Trade: The Journals of 1802–1804. Edited by Laura Peers and Theresa Schenck. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002.

- Nute, Grace Lee. The Voyageur. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1987.

- Podruchny, Carolyn. Making the Voyageur World: Travelers and Traders in the North American Fur Trade. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

- Podruchny, Carolyn and Laura Peers, eds. Gathering Places: Aboriginal and Fur Trade Histories. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2010.

- Ray, Arthur J. Indians in the Fur Trade: Their Role as Trappers, Hunters, and Middlemen in the Lands Southwest of Hudson Bay, 1660–1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974.

- Sleeper-Smith, Susan. Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001.

- Treuer, Anton. Ojibwe in Minnesota. St Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010.

- Van Kirk, Sylvia. Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur-Trade Society, 1670–1870. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980.

- Wingerd, Mary Lethert. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.