Hmong Timeline

4,000-3,000 BCE

Oral tradition and evidence from archives and archaeological finds suggest that Hmong people originated near the Yellow and Yangtze rivers in China. Known as industrious farmers, the Hmong are credited with being among the first people to cultivate rice and to spread this staple throughout Asia. For the next several thousand years, the Hmong struggled to gain independence as Imperial China suppressed uprisings by smaller kingdoms and ethnic minorities in the quest to unite all people of China

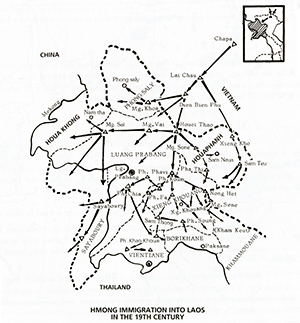

Around 1790 to the 1860s

For centuries, the Hmong lived autonomously in remote areas of China, retaining a unique culture despite ongoing conflicts with Imperial China. Major uprisings, such as the Miao Rebellion (1795–1806) and the Taiping Rebellion (1850-64), occurred when Chinese rulers used military might to suppress the Hmong and other ethnic minorities. These conflicts resulted in a mass exodus by the Hmong into the mountainous regions of Southeast Asia—areas known today as Laos, Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, and Vietnam.

We always knew that our history was rooted in China. However, our ancestors never got along with the Imperial Chinese. They invaded our lands. Killed our people. This went on for hundreds of years. Many Hmong leaders and their families, including my great-grandparents, moved to Laos to escape being persecuted.

Cher Cha Vang, former military major and Hmong leader, Minneapolis, interview 2006

From Hmong at the Turning Point, 1993, by Dr. Yang Dao

1893-1940

In 1893, the Kingdom of Laos became a “protectorate,”or colony, of France, as part of what was known as French Indochina. The Hmong of Laos—perhaps as many as 30,000—were heavily taxed and oppressed by French and Laotian authorities. Xieng Khouang Province was the region of greatest Hmong influence in Laos. Other provinces that had concentration of Hmong includes Luang Prabang, Phongsaly, Sam Neua, and Xayaboury. By the early 1900s, the French and Laotian authorities were letting Hmong leaders, especially from the Moua, Lee, and Yang clans, deal directly with Hmong issues.

The Laotians wanted one kilo of opium per household. . . . They even took our livestock and money. . . . Some of the parents had to sell their children to pay for the taxes. Some parents were so upset they committed suicide by taking poison.

Pa Seng Thao, in Paul Hillmer, A People’s History of the Hmong, 2010

Since the beginning, the King of Xieng Khouang had always given the authority to the Chao Mouang [Mayor] of Ban Bane to administer the Hmong people in the Nong Het area. When the Hmong people increased in numbers and became prosperous, an old Chao Mouang of Ban Bane decided to nominate a Hmong person to be the Phutong (local official) to help him administer the Hmong people in the Hmong villages.

The Hmong Phutong worked very hard. He quickly settled every small dispute so that the villages could make their living peacefully. The Hmong people were very happy. They like the Phutong very much and honored him like a father.

Touby Lyfoung, in Dr. Touxa Lyfoung’s Touby Lyfoung: An authentic account of the life of a Hmong man in the troubled land of Laos (1996)

Portrait of a Hmong girl in Laos, 1920s. Courtesy Noah Vang, St. Paul

1940-45: World War II

During World War II--known by elders in the Hmong community as the Japanese War--the Hmong of Laos were divided into two factions due to internal clan conflicts. Most Hmong stayed loyal to the French and the Royal Lao Government; the rest joined the Communist Party, Neo Lao Hak Xat (renamed Pathet Lao). The pro-French Hmong showed fierceness against the Japanese by rescuing the king in Luang Prabang, who was being held by Japanese forces while they were extending their reach over Southeast Asia. As a result, several Hmong leaders won national political positions. Touby Lyfoung, with his brothers Toulia Lyfoung and Tougeu Lyfoung, were the first successful Hmong politicians in the Lao government. Under Touby Lyfoung’s leadership, Hmong assisted and hid French soldiers from the Japanese military. The Hmong were officially recognized as citizens of Laos in 1947.

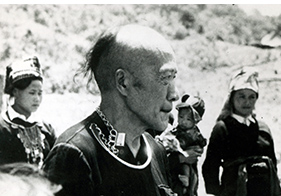

Hmong elder in the Plain of Jars, Xieng Khouang Province, Laos, early 1900s. Courtesy Carl Lorence, Pennsylvania

1945-54

At the end of World War II, the French attempted to reassert control over their former colonies in Southeast Asia, but were fiercely opposed by Chinese-backed Communist forces in Vietnam and Laos. Many Hmong were drawn into the new war that engulfed the entire region. During the 1954 battle at Dien Bien Phu, Vietnam, about 500 Hmong soldiers were sent from Laos to assist the French. They were days away from the front line when the French surrendered to the Communist Viet Minh; this effectively ended French rule in Southeast Asia. The Geneva Accords in 1954 divided Vietnam into two separate countries. North Vietnam was formed as a communist country, while South Vietnam, a democracy, soon gained American support after the French. Within Hmong society, clan leaders became proactive both politically and militarily in the Lao government.

Hmong soldiers, led by Touby Lyfoung (second from left), with a French officer during French occupation of Indochina in Xiengkhoungville, Laos, September 1945. Courtesy Vajtsuas Shouayang, France

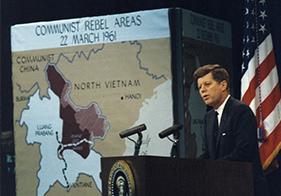

1961

A coup d'état in 1960 in the Lao capital, Vientiane, deepened the country’s political instability. As a result, newly elected US president John F. Kennedy authorized the recruitment of ethnic minorities in Laos to participate in covert military operations against the spread of communism. CIA agent Bill Lair met with the young Hmong military officer Vang Pao to discuss supporting US objectives in Laos. A sharp increase in the number of Hmong troops, supported by American military and CIA advisers, along with huge drops of military supplies, signaled the start of what is now called the Secret War.

I want to make it clear to the American people, and to all of the world, that all we want in Laos is peace, not war—a truly neutral government, not a cold war pawn, a settlement concluded at the conference table and not on the battlefield. Our response will be made in close cooperation with our allies and the wishes of the Laotian government. We will not be provoked, trapped, or drawn into this or any other situation but I know that every American will want his country to honor its obligations to the point that freedom and security of the free world and ourselves may be achieved.

Pres. John F. Kennedy, Press conference, State Department, March 23, 1961

Communism was spreading in our part of the world—pouring into Laos, Cambodia, and South Vietnam. We had to find a way to stop them. The US had the vision to stop them from spreading into these countries. I aligned with the US because they were the most powerful country in the world at that time. The United States had won World War I and World War II, and I assumed that winning the Vietnam War would be no problem.”

Gen. Vang Pao, St. Paul, interview 2006

Pres. John F. Kennedy in March 1961. In the early years of his presidency, he also dispatched CIA personnel to Laos. The maroon-color shaded region on the map was MR II, commanded by Gen. Vang Pao, and was the area where the heaviest fighting in Laos took place. Courtesy The John F. Kennedy Library

1963

Of the 300,000 Hmong people living in Laos, more than 19,000 men were recruited into the CIA-sponsored secret operation known as Special Guerrilla Units (SGU) while some enlisted as Forces Armees du Royaume, the Laotian royal armed forces. Each soldier was paid an equivalent of three dollars a month. Air America—the “private” airline contracted by the CIA—dropped 40 tons of food per month. King Sisavang Vatthana of Laos appointed Touby Lyfoung to his advisory board.

The US funded new schools throughout the remote regions of Laos, which opened opportunities to Hmong girls. As the war escalated, some Hmong girls were trained as nurses and medics to care for wounded soldiers.

In my generation, education was only for the privileged and wealthy families. We had no money so I taught myself to read and write in Lao. Where we lived, girls did not attend schools until the late 1950s. When the war started in our country, the Americans began building small schools in nearby villages where both boys and girls could go learn. For some students, they walked as far as half a day just to get an education.

Lao Thai Vang, former mayor of Hong Nong, Sam Neua Province, Laos, 1965-75. St. Paul, interview 2009

Striped Hmong girls in northern Laos, early 1960s. Courtesy Vint Lawrence, Connecticut, and Noah Vang, St. Paul

1968-69

In the two worst years of the both the American War in Vietnam and the Secret War in Laos, 18,000 Hmong soldiers were killed in combat, in addition to thousands more civilian casualties. The March 1968 assault by North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao forces on the top-secret airbase at Phou Pha Thi—known to the CIA as “Lima Site 85”—resulted in the deaths of 12 US Air Force personnel, and many more Hmong and Thai soldiers.

By 1969, Hmong troop strength was nearing 40,000. Under the new administration of Pres. Richard Nixon, U.S. bombing of Laos escalated, and Congress learned of CIA covert military operations in Laos.

Before the war all the men in our village worked hard and supported their families. We had peace. There was no war. All of a sudden, our lives changed. The men began to disappear. They went to fight for Gen. Vang Pao, for the Americans. Most of our husbands never returned home. My husband died in the war. We told Gen. Vang Pao that we wanted the war to end and to end all the killing. He also wanted the war to end.Youa Lee, St. Paul, interview 2011

A short time ago we rounded up 300 fresh recruits. Thirty percent were 14 years old or less, and ten of them were only ten years old. Another 30 percent were 15 or 16. The remaining 40 percent were 45 or over. Where were the ones in between? I’ll tell you—they’re all dead.

Edgar “Pop” Buell, International Voluntary Service employee, 1968

Boy soldier in the Secret War in Laos, early 1960s. Courtesy James W. Lair, Texas, and Noah Vang, St. Paul

1971-72

By 1971, the Secret War was weighing heavily on the Hmong and the people of Laos. The estimated death toll for Hmong soldiers this year alone was 3,000, with 6,000 more wounded. More and more boys were becoming involved; the average age of Hmong recruits that year was 15. Throughout 1971, Long Cheng air base was pounded constantly by artillery from massive guns hidden in the surrounding hills. Meanwhile, American opposition to the wars in Southeast Asia mounted, even as Pres. Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger spoke of “peace with honor” and “the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Then, our objectives in supporting the United States to fight the war in Laos were: first, we had to stop the North Vietnamese from sending troops and supplies into South Vietnam using the Ho Chi Minh Trail; second, to rescue downed American pilots; and third, to defend and protect the radar site at Phou Pha Thi.

Col. Ly Toupao, St. Paul, interview 2006

By this time, Air America was keeping some 170,000 Hmong refugees alive with airdrops of rice, a situation that had gone on so long that Hmong children were said to believe that rice was not grown but simply fell from the sky.

Walter J. Boyne, Plain of Jars, 1970

US planes dropping food and military supplies to friendly remote military posts in Laos, early 1960s. Courtesy James W. Lair, Texas

1973

In February, a cease-fire and political peace treaty was signed in Paris, requiring the US and all foreign powers to withdraw all military activities from Laos. More than 120,000 Hmong became refugees in their own homelands. 18,000 Hmong soldiers were left in Laos, representing nearly three-quarters of the irregular forces. About 50,000 Hmong civilians had been killed or wounded in the war.

On September 14, the Vientiane Agreement was signed, giving the Communist Pathet Lao more control of the Lao government.

I hope you all believe me when I say that your welfare has always been, is now, and will always continue to be of the highest priority interest for me and my fellow USA co-workers. I still remember that I and, perhaps, other Americans who are representatives of the United States government, have promised you, the Hmong People, that if you fight for us, if we win, things will be fine. But if we lose, we will take care of you.

Jerry (“Hog”) Daniels, CIA case officer and adviser to the Hmong and Gen. Vang Pao. From A Letter From Jerry Daniels (1941-1982)

Yang Long giving instructions to soldiers who will be trained as radio operators in Long Cheng air base in Laos, late 1960s. Courtesy Yang Long, St. Paul

1975

North Vietnamese Army and Pathet Lao captured Royal Lao positions, and South Vietnam fell to Communist North Vietnam. Gen. Vang Pao and about 2,500 Hmong military forces and family members were airlifted from Long Cheng air base to Thailand. As many as 30,000 other Hmong crowded into Long Cheng, hoping for escape.

By the war’s end, between 30,000 and 40,000 Hmong soldiers had been killed in combat, and between 2,500 and 3,000 were missing in action. An estimated one-fourth of all Hmong men and boys died fighting the Communist Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese Army. The official US military death total in Vietnam exceeded 58,000.

For 10 years, Vang Pao’s soldiers held the growing North Vietnamese forces to approximately the same battlelines they held in 1962. And significantly for Americans, the 70,000 North Vietnamese engaged in Laos were not available to add to the forces fighting Americans and South Vietnamese in South Vietnam.

William E. Colby, CIA director 1973-76, speech 1996

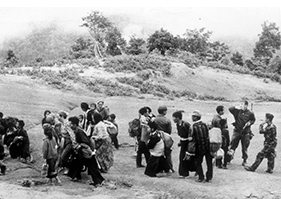

Since 1961, the war had displaced hundreds of thousands of Hmong and other ethnic minority families and often they were relocated to locations developed by US aid workers. Photo late 1960s. Courtesy Capt. Vang Neng, St. Paul

1975-2015

After overthrowing the Laotian monarchy, the Pathet Lao launched an aggressive campaign to capture or kill Hmong soldiers and families who sided with the CIA. Thousands of Hmong were evacuated or escaped on their own to Thailand. Thousands more who had already gone to live deep in the jungle were left to fend for themselves, which led to the creation of the Chao Fa and Neo Hom freedom fighters movements. Many men also took up arms again to protect their families as they crossed the heavily patrolled Mekong River to safety in Thailand.

Hmong began moving into refugee camps overseen by non-governmental organizations such as the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the International Rescue Committee, Refugees International ,and the Thai Ministry of the Interior. The first Hmong family to resettle in Minnesota arrived in November 1975. The largest wave came after the passage of the US Refugee Act of 1980.

In 2004, the Buddhist monastery at Wat Tham Krabok—the last temporary shelter for 15,000 Hmong remaining in Thailand—closed. This “last wave” came to the US, with as many as 5,000 settling in established Minnesota Hmong communities.

The 2010 census recorded more than 260,000 Hmong in the United States. More than 66,000 of that number lived in Minnesota, most of them in or near the Twin Cities—the largest urban population of Hmong in America.

Here were thousands of Hmong, many of whom spoke American military lingo and had names likes ‘Lucky’ and ‘Judy’ and ‘Bison’ and who had been soldiers, radio operators, pilots, and CIA operatives in a war unknown to the American public. This was unacceptable. How could the U.S. abandon these people? If the United States owed gratitude to anyone in Southeast Asia it was the Hmong.

Lionel Rosenblatt, head of the Refugees International, in Larry Clinton Thompson’s Refugee Workers in the Indochina Exodus, 1975-1982 (2010)

Toward the middle of May 1975, thousands of Hmong swarmed into the air base at Long Cheng in hopes of being evacuated. The decision to airlift Gen. Vang Pao out of Laos, along with other high-ranking military officers and their families, came from top US government officials. About 2,500 people were evacuated to Thailand. Those left behind had to trek on foot. Courtesy Thua Vang, California