Arthur and Edith Lee House, Minneapolis

Bibliography

106 Group. “Minneapolis African American Historic and Cultural Context Study.” February 2025.

https://lims.minneapolismn.gov/download/Agenda/7094/5112/2025-02-10_MinneapolisAAContextStudy.pdf

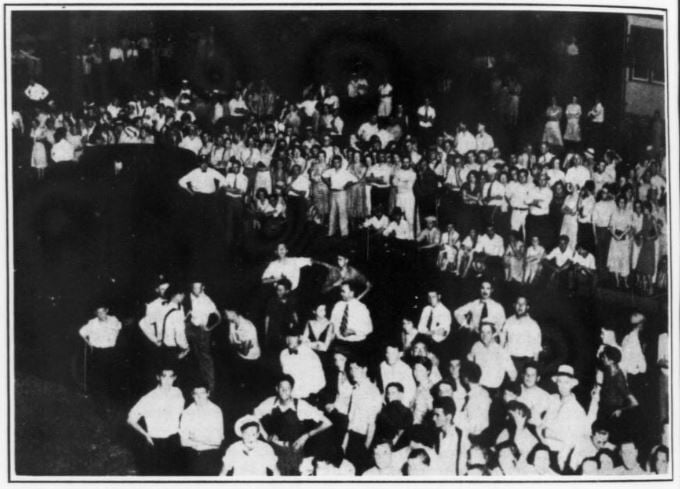

"4,000 Assemble Near Negro' s Home." Minneapolis Tribune, July 17, 1931.

Adelsman, H. Lynn. "Desegregating South Minneapolis Housing TilsenBilt Homes of 1954." Hennepin History 64, no. 2 (Spring 2005): 24–33.

https://hennepinhistory.org/tilsenbilt

Fritz, Laurel, and Greg Donofrio. “Arthur and Edith Lee House.” National Register of Historic Places nomination file, May 21, 2014. State Historic Preservation Office, St. Paul.

https://ncshpo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Arthur-and-Edith-Lee-House-NRHP-NominationLR.pdf

South Minneapolis History: The Arthur and Edith Lee Family (Arthur and Edith Lee House marker). Historical Marker Database.

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=205392

City of Minneapolis. “Lee House.”

https://www.minneapolismn.gov/resident-services/property-housing/preservation/landmarks-districts/landmarks/arthur-and-edith-lee-house

"Crowd of 3,000 Renews Attack on Negro' s Home." Minneapolis Tribune, July 16, 1931.

"Home Stoned in Race Row: Sale of House to Negro Stirs Neighborhood." Minneapolis Tribune, July 15, 1931.

Jim Crow of the North: Redlining and Racism in Minnesota. Directed by Daniel Pierce Bergin. Twin Cities PBS, 2019.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XWQfDbbQv9E

“Lee to Keep Home, Attorney Avows.” Minneapolis Journal, July 20, 1931.

Sluss, Jacquelin. “Lena O. Smith House.” National Register of Historic Places nomination file, July 16, 1990. Minnesota State Historic Preservation Office, St. Paul.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/91001472

"Throng Still Perils Negro in Mill City." St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 17, 1931.

https://newspaperhub.mnhs.org/?a=d&d=sppp19310717

Chronology

1923

1927

late June 1931

July 1931

July 11

July 14

July 15

July 16

July 18

July 20

late 1933

2011

2014

2016

Bibliography

106 Group. “Minneapolis African American Historic and Cultural Context Study.” February 2025.

https://lims.minneapolismn.gov/download/Agenda/7094/5112/2025-02-10_MinneapolisAAContextStudy.pdf

"4,000 Assemble Near Negro' s Home." Minneapolis Tribune, July 17, 1931.

Adelsman, H. Lynn. "Desegregating South Minneapolis Housing TilsenBilt Homes of 1954." Hennepin History 64, no. 2 (Spring 2005): 24–33.

https://hennepinhistory.org/tilsenbilt

Fritz, Laurel, and Greg Donofrio. “Arthur and Edith Lee House.” National Register of Historic Places nomination file, May 21, 2014. State Historic Preservation Office, St. Paul.

https://ncshpo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Arthur-and-Edith-Lee-House-NRHP-NominationLR.pdf

South Minneapolis History: The Arthur and Edith Lee Family (Arthur and Edith Lee House marker). Historical Marker Database.

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=205392

City of Minneapolis. “Lee House.”

https://www.minneapolismn.gov/resident-services/property-housing/preservation/landmarks-districts/landmarks/arthur-and-edith-lee-house

"Crowd of 3,000 Renews Attack on Negro' s Home." Minneapolis Tribune, July 16, 1931.

"Home Stoned in Race Row: Sale of House to Negro Stirs Neighborhood." Minneapolis Tribune, July 15, 1931.

Jim Crow of the North: Redlining and Racism in Minnesota. Directed by Daniel Pierce Bergin. Twin Cities PBS, 2019.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XWQfDbbQv9E

“Lee to Keep Home, Attorney Avows.” Minneapolis Journal, July 20, 1931.

Sluss, Jacquelin. “Lena O. Smith House.” National Register of Historic Places nomination file, July 16, 1990. Minnesota State Historic Preservation Office, St. Paul.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/91001472

"Throng Still Perils Negro in Mill City." St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 17, 1931.

https://newspaperhub.mnhs.org/?a=d&d=sppp19310717