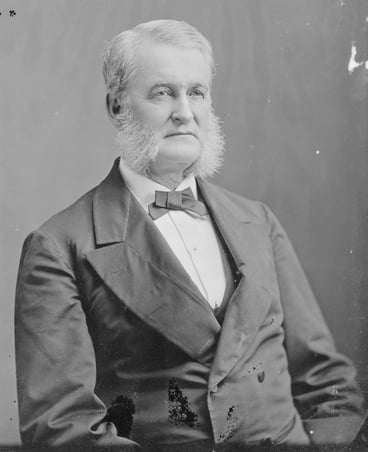

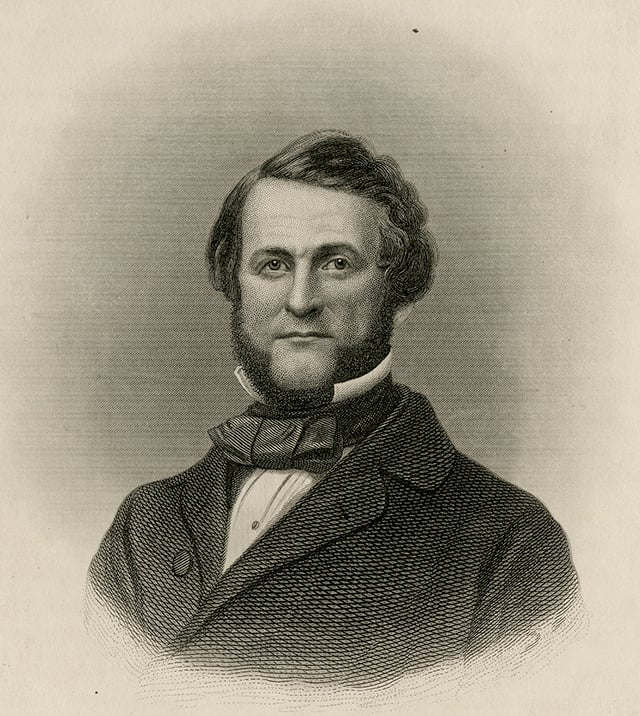

Steele, Franklin (ca. 1813–1880)

Bibliography

A/.S814

Franklin Steele papers, 1839–1888

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Correspondence and financial records of this Minnesota lumberman and entrepreneur.

DeCarlo, Peter. Fort Snelling at Bdote: A Brief History. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2020.

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vol. 1. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1956.

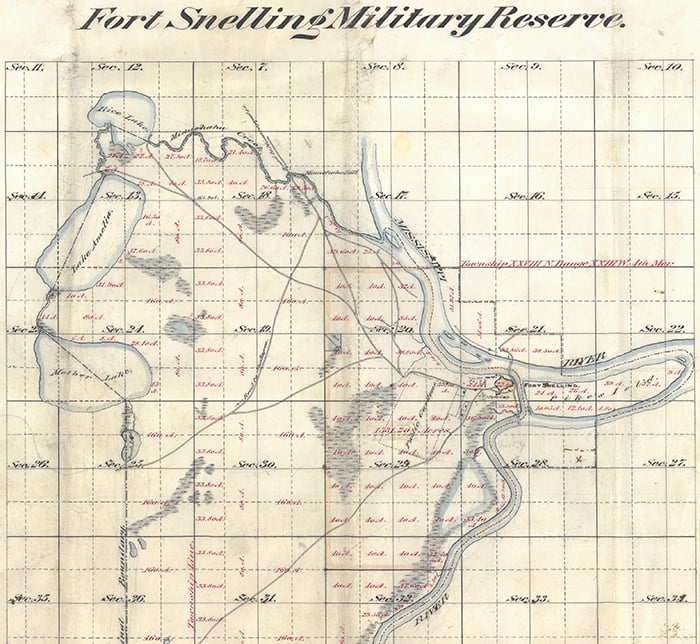

—————. The Sale of Fort Snelling, 1857. Minnesota Historical Society, 1915.

“Fort Snelling Investigation.” H.R. Rep. No. 351, 35th Cong., 1st Sess. (1858).

https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset/1416

Franklin Steele to H. Reynolds, May 19, 1860. Box 6, folder 3 of the Franklin Steele papers, 1839–1888 (A/.S814), Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul.

“History of the Board of Regents.” University of Minnesota.

https://regents.umn.edu/history-board-regents

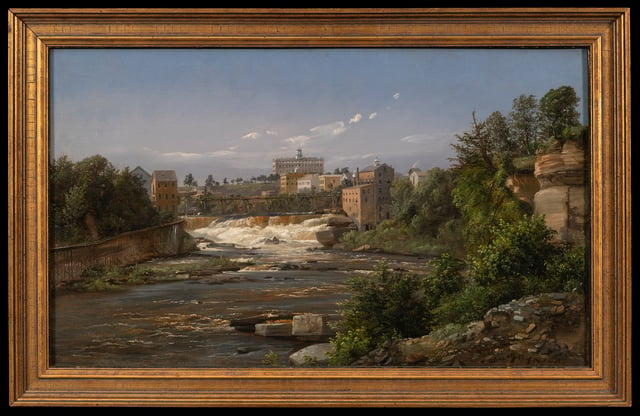

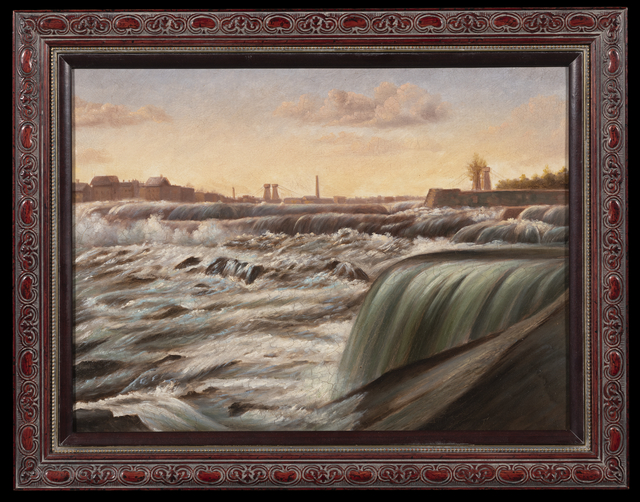

Kane, Lucille M. The Waterfall that Built a City. Minnesota Historical Society, 1966.

Loehr, Rodney C. “Franklin Steele, Frontier Businessman.” Minnesota History 27, no. 4 (December 1946): 309–318.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/27/v27i04p309-318.pdf

Millikan, William. “The Great Treasure of the Fort Snelling Prison Camp.” Minnesota History 62, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 4–17.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/62/v62i01p004-017.pdf

Monjeau-Marz, Corinne L. The Dakota Indian Internment At Fort Snelling, 1862–1864. Prairie Smoke Press, 2006.

Neill, Edward D. History of Hennepin County and the City of Minneapolis, including the Explorers and Pioneers of Minnesota. North Star Publishing Company, 1881.

https://archive.org/details/cu31924006600484

OH 183.21

Oral history interview with Ed LaBelle, June 7, 2012

US–Dakota War of 1862 Oral History Project Oral History Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Ed LaBelle (Sisseton–Wahpeton Dakota) describes his personal history, including his family’s experience in the US–Dakota War of 1862.

https://www.mnhs.org/search/collections/record/ede90586-ed03-4332-83ed-3950e635d62d

Osman, Steven E. Fort Snelling and the Civil War. Ramsey County Historical Society, 2017.

Parmenter, Jon. “Flipped Scrip, Flipping the Script: The Morrill Act of 1862, Cornell University, and the Legacy of Nineteenth-Century Indigenous Dispossession.” Cornell University and Indigenous Dispossession Project, October 1, 2020.

https://blogs.cornell.edu/cornelluniversityindigenousdispossession/2020/10/01/flipped-scrip-flipping-the-script-the-morrill-act-of-1862-cornell-university-and-the-legacy-of-nineteenth-century-indigenous-dispossession

Ress, David. The Half Breed Tracts in Early National America: Changing Concepts of Land and Place. Springer Nature, 2019.

Ross, Drew M. Becoming the Twin Cities: Swindles, Schemes, and Enduring Rivalries. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2025.

Smith, Hampton. Confluence: A History of Fort Snelling. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2021.

Stevens, John H. Personal Recollections of Minnesota and its People and Early History of Minneapolis. N.p., 1900.

https://archive.org/details/personalrecollec00stev/page/n3/mode/2up

“Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes, etc., 1830.” July 15, 1830.

https://treaties.okstate.edu/treaties/treaty-with-the-sauk-and-foxes-etc-1830-0305

Welles, H. T. Autobiography And Reminiscences. Vol. 2. M. Robinson, 1899.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89076993872

Chronology

1813 or 1814

1837

1838

1851

1854

1855

1857

1858

1858

1860

1861–65

1862–63

1862–63

1868

1880

Bibliography

A/.S814

Franklin Steele papers, 1839–1888

Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Correspondence and financial records of this Minnesota lumberman and entrepreneur.

DeCarlo, Peter. Fort Snelling at Bdote: A Brief History. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2020.

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vol. 1. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1956.

—————. The Sale of Fort Snelling, 1857. Minnesota Historical Society, 1915.

“Fort Snelling Investigation.” H.R. Rep. No. 351, 35th Cong., 1st Sess. (1858).

https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset/1416

Franklin Steele to H. Reynolds, May 19, 1860. Box 6, folder 3 of the Franklin Steele papers, 1839–1888 (A/.S814), Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul.

“History of the Board of Regents.” University of Minnesota.

https://regents.umn.edu/history-board-regents

Kane, Lucille M. The Waterfall that Built a City. Minnesota Historical Society, 1966.

Loehr, Rodney C. “Franklin Steele, Frontier Businessman.” Minnesota History 27, no. 4 (December 1946): 309–318.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/27/v27i04p309-318.pdf

Millikan, William. “The Great Treasure of the Fort Snelling Prison Camp.” Minnesota History 62, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 4–17.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/62/v62i01p004-017.pdf

Monjeau-Marz, Corinne L. The Dakota Indian Internment At Fort Snelling, 1862–1864. Prairie Smoke Press, 2006.

Neill, Edward D. History of Hennepin County and the City of Minneapolis, including the Explorers and Pioneers of Minnesota. North Star Publishing Company, 1881.

https://archive.org/details/cu31924006600484

OH 183.21

Oral history interview with Ed LaBelle, June 7, 2012

US–Dakota War of 1862 Oral History Project Oral History Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Ed LaBelle (Sisseton–Wahpeton Dakota) describes his personal history, including his family’s experience in the US–Dakota War of 1862.

https://www.mnhs.org/search/collections/record/ede90586-ed03-4332-83ed-3950e635d62d

Osman, Steven E. Fort Snelling and the Civil War. Ramsey County Historical Society, 2017.

Parmenter, Jon. “Flipped Scrip, Flipping the Script: The Morrill Act of 1862, Cornell University, and the Legacy of Nineteenth-Century Indigenous Dispossession.” Cornell University and Indigenous Dispossession Project, October 1, 2020.

https://blogs.cornell.edu/cornelluniversityindigenousdispossession/2020/10/01/flipped-scrip-flipping-the-script-the-morrill-act-of-1862-cornell-university-and-the-legacy-of-nineteenth-century-indigenous-dispossession

Ress, David. The Half Breed Tracts in Early National America: Changing Concepts of Land and Place. Springer Nature, 2019.

Ross, Drew M. Becoming the Twin Cities: Swindles, Schemes, and Enduring Rivalries. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2025.

Smith, Hampton. Confluence: A History of Fort Snelling. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2021.

Stevens, John H. Personal Recollections of Minnesota and its People and Early History of Minneapolis. N.p., 1900.

https://archive.org/details/personalrecollec00stev/page/n3/mode/2up

“Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes, etc., 1830.” July 15, 1830.

https://treaties.okstate.edu/treaties/treaty-with-the-sauk-and-foxes-etc-1830-0305

Welles, H. T. Autobiography And Reminiscences. Vol. 2. M. Robinson, 1899.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89076993872