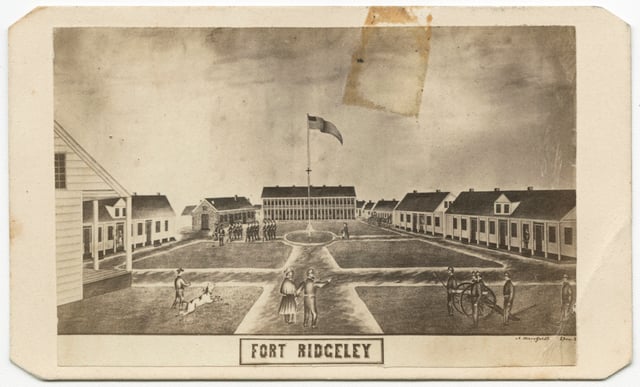

Fort Ridgely

Bibliography

109.K.19.8F

Fort Ridgely Monument files, 1895, 1907–1910

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Correspondence, contracts, drawings, plats, and reports concerning the renovation of the Fort Ridgely Monument site between 1909 and 1910.

Anderson, Rolf T. “Fort Ridgely State Park CCC/Rustic Style Historic Resources.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form, September 9, 1988. State Historic Preservation Office, St. Paul.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/ece13fee-d0de-45db-bde9-9fb4a0c94c3b

Annual Report of the Commissioner of the Office of Indian Affairs for the Year 1852 . Government Printing Office, 1853. Arnott, Sigrid, and David L. Maki. “Forts on Burial Mounds: Interlocked Landscapes of Mourning and Colonialism at the Dakota-Settler Frontier, 1860–1876.” Historical Archaeology 53 (2019): 153–169.

Babcock, Willoughby M. “Up the Minnesota Valley to Fort Ridgely in 1853.” Minnesota History 11, no. 2 (June 1930): 161–184.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/11/v11i02p161-184.pdf

Beck, Paul. Soldiers, Settler, and Sioux: Fort Ridgely and the Minnesota River Valley 1853–1867 . Pine Hills Press, 2000. Printed for the Center for Western Studies, Augustana College.

Berthelette, Scott. Heirs of an Ambivalent Empire: French-Indigenous Relations and the Rise of the Métis in the Hudson Bay Watershed. McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2022. Breese, Samuel. Iowa and Wisconsin. Chiefly from the Map of N. J. Nicollet . No scale. Harper & Brothers, 1845. David Rumsey Map Collection.

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/ng0t37

Cross, John. “Ring of Fire.” Mankato Free Press, July 6, 2006.

https://www.mankatofreepress.com/news/local_news/ring-of-fire/article_952d2522-72a8-57af-88c3-5b449d526e31.html

Ellig, Tom. Conversation with the author, October 27, 2025.

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vol. 1. Minnesota Historical Society, 1922. Fort Ridgely National Park and Historical Society. Articles of Incorporation and By-laws of the Fort Ridgely National Park and Historical Association. Sleepy Eye Dispatch, 1899.

Gibbon, Guy. Archaeology of Minnesota: The Prehistory of the Upper Mississippi River Region. University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Gray, Maggie. “No Plans to Reopen Fort Ridgely Interpretive Center.” The Journal (Brown County), April 11, 2025.

https://www.nujournal.com/news/local-news/2025/04/11/no-plans-to-reopen-fort-ridgely-interpretative-center

Grossman, John. “Fort Ridgely.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form, March 24, 1970. State Historic Preservation Office, St. Paul.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/f755de7b-f20c-4d64-8fda-970ffcde0839

Journal of the Council of Minnesota During the Fourth Session of the Legislative Assembly . Joseph R. Brown, Territorial Printer, 1853.

Kappler, Charles Joseph, ed. Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Vol. 2. Government Printing Office, 1904.

Leonard, Ben. Conversation with the author, October 23, 2025.

M359 Fort Ridgely documents, 1853–1867 Manuscript Microfilm, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul Description: Post-letters-sent books (1854–1860), order books (1856–1860, 1866–1867), morning reports (1856–1867), and a set of incoming correspondence, orders, reports, accounts, and inventories (1853–1859).

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Fort Ridgely State Park Management Plan Amendment: Boundary Expansion, Horse Campground and Trail Connections . January 2006.

https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/input/mgmtplans/parks/fort-ridgely/fort-ridgely-amend-2006.pdf

——— . Fort Ridgely State Park Management Plan Amendment . June 20, 2017.

https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/input/mgmtplans/parks/fort-ridgely/fort-ridgely-golf-course-repurposing-2017.pdf

Myles, Marlena. “Dakhóta Thamákhočhe: Mnísota Wakpá Makhósmaka.” No scale.

https://marlenamyl.es/project/dakota-land-map

P762 Fort Ridgely State Park and Historical Association papers, 1888–1956 Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul Description: The correspondence, clippings, and other papers of the Fort Ridgely State Park and Historical Association officers Charles H. and Frank Hopkins, relating to the organization’s promotion of the creation and development of Fort Ridgely State Park (Nicollet County).

P2892 Fort Ridgely records, 1870–1880 Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul Description: Volume prepared in the office of the US Adjutant General from the archives of the War Department. Includes one map.

Pierpaoli, Paul G., Jr. “Fort Ridgely.” In American Civil War: A State-by-State Encyclopedia , Vol. 1, edited by Spencer C. Tucker and Paul G. Pierpaoli, Jr., 403–404. ABC-CLIO, 2015.

Prucha, Francis Paul. “The Settler and the Army in Frontier Minnesota.” Minnesota History 29, no. 3 (September 1948): 231–246.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/29/v29i03p231-246.pdf

Pope, John. Map of the Territory of Minnesota, Exhibiting the Route of the Expedition to the Red River of the North, in the Summer of 1849 . 1:1,267,200 scale. Minnesota Land Surveyors Association, 1849. David Rumsey Map Collection.

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/986j3s

Randall, Benjamin Hoyt. A Brief Sketch and History of Fort Ridgely . Fairfax Crescent Printing, 1896.

Renville, Mary Butler. Dispatches from the Dakota War: A Thrilling Narrative of Indian Captivity. Edited by Carrie Reber Zeman and Kathryn Zabelle Derounian-Stodola. University of Nebraska Press, 2012. Tanner, Henry S. “Iowa.” A New Universal Atlas Containing Maps of the Various Empires, Kingdoms, States and Republics Of The World . 1:1,340,000 scale. H. S. Tanner, 1842. David Rumsey Map Collection.

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/598iui

Westerman, Gwen, and Bruce White. Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012.

Wilson, Diane. “Dakota Homecoming.” American Indian Quarterly 28, no. 1/2 (Winter–Spring 2004): 340–348.

Wilson, Waziyatawin Angela, ed. In the Footsteps of Our Ancestors: The Dakota Commemorative Marches of the 21st Century. Living Justice Press, 2006.

Wingerd, Mary Letherd. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

“Working Year-Round to Develop the Park: The New Deal and Fort Ridgely State Park.” Historical Marker Database.

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=71881

Young, J. H. “Map of Minnesota Territory.” Cowperthwait, Desilver & Butler, 1850. A New Universal Atlas Containing Maps of the Various Empires, Kingdoms, States and Republics of The World. 1855. 1:2,400,000 scale. David Rumsey Map Collection.

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/a6cg31

Young, Laurie, Carole Reamer Braun, and Peter Buesseler. A Summary of the Fort Ridgely State Park Management Plan. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Office of Planning, 1983.

https://www.lrl.mn.gov/edocs/edocs?oclcnumber=10048536

Chronology

1852

March 30, 1853

June 27, 1853

July 11, 1853

August 17, 1862

August 20 and 22, 1862

August 27 and 28, 1863

February 16, 1863

1867

1868

1870

1871

1873

1895

1913

1970

Bibliography

109.K.19.8F

Fort Ridgely Monument files, 1895, 1907–1910

State Archives Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Correspondence, contracts, drawings, plats, and reports concerning the renovation of the Fort Ridgely Monument site between 1909 and 1910.

Anderson, Rolf T. “Fort Ridgely State Park CCC/Rustic Style Historic Resources.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form, September 9, 1988. State Historic Preservation Office, St. Paul.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/ece13fee-d0de-45db-bde9-9fb4a0c94c3b

Annual Report of the Commissioner of the Office of Indian Affairs for the Year 1852 . Government Printing Office, 1853. Arnott, Sigrid, and David L. Maki. “Forts on Burial Mounds: Interlocked Landscapes of Mourning and Colonialism at the Dakota-Settler Frontier, 1860–1876.” Historical Archaeology 53 (2019): 153–169.

Babcock, Willoughby M. “Up the Minnesota Valley to Fort Ridgely in 1853.” Minnesota History 11, no. 2 (June 1930): 161–184.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/11/v11i02p161-184.pdf

Beck, Paul. Soldiers, Settler, and Sioux: Fort Ridgely and the Minnesota River Valley 1853–1867 . Pine Hills Press, 2000. Printed for the Center for Western Studies, Augustana College.

Berthelette, Scott. Heirs of an Ambivalent Empire: French-Indigenous Relations and the Rise of the Métis in the Hudson Bay Watershed. McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2022. Breese, Samuel. Iowa and Wisconsin. Chiefly from the Map of N. J. Nicollet . No scale. Harper & Brothers, 1845. David Rumsey Map Collection.

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/ng0t37

Cross, John. “Ring of Fire.” Mankato Free Press, July 6, 2006.

https://www.mankatofreepress.com/news/local_news/ring-of-fire/article_952d2522-72a8-57af-88c3-5b449d526e31.html

Ellig, Tom. Conversation with the author, October 27, 2025.

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vol. 1. Minnesota Historical Society, 1922. Fort Ridgely National Park and Historical Society. Articles of Incorporation and By-laws of the Fort Ridgely National Park and Historical Association. Sleepy Eye Dispatch, 1899.

Gibbon, Guy. Archaeology of Minnesota: The Prehistory of the Upper Mississippi River Region. University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Gray, Maggie. “No Plans to Reopen Fort Ridgely Interpretive Center.” The Journal (Brown County), April 11, 2025.

https://www.nujournal.com/news/local-news/2025/04/11/no-plans-to-reopen-fort-ridgely-interpretative-center

Grossman, John. “Fort Ridgely.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form, March 24, 1970. State Historic Preservation Office, St. Paul.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/f755de7b-f20c-4d64-8fda-970ffcde0839

Journal of the Council of Minnesota During the Fourth Session of the Legislative Assembly . Joseph R. Brown, Territorial Printer, 1853.

Kappler, Charles Joseph, ed. Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Vol. 2. Government Printing Office, 1904.

Leonard, Ben. Conversation with the author, October 23, 2025.

M359 Fort Ridgely documents, 1853–1867 Manuscript Microfilm, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul Description: Post-letters-sent books (1854–1860), order books (1856–1860, 1866–1867), morning reports (1856–1867), and a set of incoming correspondence, orders, reports, accounts, and inventories (1853–1859).

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Fort Ridgely State Park Management Plan Amendment: Boundary Expansion, Horse Campground and Trail Connections . January 2006.

https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/input/mgmtplans/parks/fort-ridgely/fort-ridgely-amend-2006.pdf

——— . Fort Ridgely State Park Management Plan Amendment . June 20, 2017.

https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/input/mgmtplans/parks/fort-ridgely/fort-ridgely-golf-course-repurposing-2017.pdf

Myles, Marlena. “Dakhóta Thamákhočhe: Mnísota Wakpá Makhósmaka.” No scale.

https://marlenamyl.es/project/dakota-land-map

P762 Fort Ridgely State Park and Historical Association papers, 1888–1956 Manuscripts Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul Description: The correspondence, clippings, and other papers of the Fort Ridgely State Park and Historical Association officers Charles H. and Frank Hopkins, relating to the organization’s promotion of the creation and development of Fort Ridgely State Park (Nicollet County).

P2892 Fort Ridgely records, 1870–1880 Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul Description: Volume prepared in the office of the US Adjutant General from the archives of the War Department. Includes one map.

Pierpaoli, Paul G., Jr. “Fort Ridgely.” In American Civil War: A State-by-State Encyclopedia , Vol. 1, edited by Spencer C. Tucker and Paul G. Pierpaoli, Jr., 403–404. ABC-CLIO, 2015.

Prucha, Francis Paul. “The Settler and the Army in Frontier Minnesota.” Minnesota History 29, no. 3 (September 1948): 231–246.

https://storage.googleapis.com/mnhs-org-support/mn_history_articles/29/v29i03p231-246.pdf

Pope, John. Map of the Territory of Minnesota, Exhibiting the Route of the Expedition to the Red River of the North, in the Summer of 1849 . 1:1,267,200 scale. Minnesota Land Surveyors Association, 1849. David Rumsey Map Collection.

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/986j3s

Randall, Benjamin Hoyt. A Brief Sketch and History of Fort Ridgely . Fairfax Crescent Printing, 1896.

Renville, Mary Butler. Dispatches from the Dakota War: A Thrilling Narrative of Indian Captivity. Edited by Carrie Reber Zeman and Kathryn Zabelle Derounian-Stodola. University of Nebraska Press, 2012. Tanner, Henry S. “Iowa.” A New Universal Atlas Containing Maps of the Various Empires, Kingdoms, States and Republics Of The World . 1:1,340,000 scale. H. S. Tanner, 1842. David Rumsey Map Collection.

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/598iui

Westerman, Gwen, and Bruce White. Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012.

Wilson, Diane. “Dakota Homecoming.” American Indian Quarterly 28, no. 1/2 (Winter–Spring 2004): 340–348.

Wilson, Waziyatawin Angela, ed. In the Footsteps of Our Ancestors: The Dakota Commemorative Marches of the 21st Century. Living Justice Press, 2006.

Wingerd, Mary Letherd. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

“Working Year-Round to Develop the Park: The New Deal and Fort Ridgely State Park.” Historical Marker Database.

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=71881

Young, J. H. “Map of Minnesota Territory.” Cowperthwait, Desilver & Butler, 1850. A New Universal Atlas Containing Maps of the Various Empires, Kingdoms, States and Republics of The World. 1855. 1:2,400,000 scale. David Rumsey Map Collection.

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/a6cg31

Young, Laurie, Carole Reamer Braun, and Peter Buesseler. A Summary of the Fort Ridgely State Park Management Plan. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Office of Planning, 1983.

https://www.lrl.mn.gov/edocs/edocs?oclcnumber=10048536